Places

As Bob Dylan's contemporary manifesto for the ancient art of memory, "Desolation Row" models how an artist gathers and reimagines inherited mythologies. Cinderella, Bette Davis, Romeo, Cain and Abel, the Hunchback of Notre Dame, the Good Samaritan, Ophelia, Einstein, Robin Hood, Dr. Filth, the Phantom of the Opera, Casanova, Nero's Neptune, the Titanic, and Ezra Pound and T. S. Eliot all gather in a single place. (Click here for the full song text.)

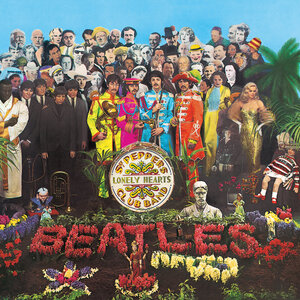

This is how a poet takes possession of the pantheon--much the same way the Beatles staked their cultural claim in the album cover portrait of Sgt. Pepper's Lonely Heart's Club Band two years later. Just as mythic tales of the sacred canon populate the walls and ceilings of cathedrals, “Desolation Row” links a chain of myths, but with reservation and revision rather than dogma:

Yes, I received your letter yesterday

(About the time the door knob broke)

When you asked how I was doing

Was that some kind of joke?

All these people that you mention

Yes, I know them, they're quite lame

I had to rearrange their faces

And give them all another name

Right now I can't read too good

Don't send me no more letters no

Not unless you mail them

From Desolation Row

Unless you are willing to visit Dylan in his perch, your message is unreadable, even offensive, because it ignores the fact that only reconstructed reality in the place of the poet's choice can preserve mythic meaning.

Unless you are willing to visit Dylan in his perch, your message is unreadable, even offensive, because it ignores the fact that only reconstructed reality in the place of the poet's choice can preserve mythic meaning. Cohen is characteristically contrite and courteous in thinking about a holy place in "Show Me the Place," a song and space we already visited in thinking about myths of origin:

Show me the place

Where you want your slave to go

Show me the place

I’ve forgotten, I don’t know

Show me the place

For my head is bending low

Show me the place

Where you want your slave to go

This is a site which is the opposite of Dylan's reworking of people and things in "Desolation Row," but the intent is similar: a single place tells the entirety of a mythic story--just like the Garden of Eden or Gethsemane or Mecca. Cohen sees all narratives flowing back towards simplicity and "the place where the suffering began." Dylan sees stories flowing from simplicity towards complexity. In either approach, their work is about making those sacred stories sing in new ways.

Sacred Stories

In his autobiographical Chronicles: Volume One, Dylan claims that a single myth serves as the touchstone not only for all of his work, but all of America as well:

I couldn't exactly put in words what I was looking for, but I began searching in principle for it, over at the New York Public Library, a monumental building with marble floors and walls, vacuous and spacious caverns, vaulted ceiling. A building that radiates triumph and glory when you walk inside….In one of the upstairs reading rooms I started reading articles in newspapers on microfilm from 1855 to about 1865 to see what daily life was like. I wasn't so much interested in the issues as intrigued by the language and rhetoric of the times....Back there, America was put on the cross, died and was resurrected. There was nothing symbolic about it. The godawful truth of that would be the all-encompassing template behind everything I would write….I crammed my head full of as much of this stuff as I could stand and locked it away in my mind out of sight, left it alone. Figured I could send a truck back for it later.

Recorded during the period of Infidels but released years later, "Blind Willie McTell" vividly demonstrates how a single story serves as a font for a flow of related stories that ultimately define a mythic vision:

Seen the arrow on the doorpost

Saying, “This land is condemned

All the way from New Orleans

To Jerusalem”

I traveled through East Texas

Where many martyrs fell

And I know no one can sing the blues

Like Blind Willie McTell

All the way from New Orleans

To Jerusalem”

I traveled through East Texas

Where many martyrs fell

And I know no one can sing the blues

Like Blind Willie McTell

|

| Blind Willie McTell |

As they were taking down the tents

The stars above the barren trees

Were his only audience

Them charcoal gypsy maidens

Can strut their feathers well

But nobody can sing the blues

Like Blind Willie McTell

See them big plantations burning

Hear the cracking of the whips

Smell that sweet magnolia blooming

See the ghosts of slavery ships

I can hear them tribes a-moaning

Hear that undertaker’s bell

Nobody can sing the blues

Like Blind Willie McTell

Hear the cracking of the whips

Smell that sweet magnolia blooming

See the ghosts of slavery ships

I can hear them tribes a-moaning

Hear that undertaker’s bell

Nobody can sing the blues

Like Blind Willie McTell

There’s a woman by the river

With some fine young handsome man

He’s dressed up like a squire

Bootlegged whiskey in his hand

There’s a chain gang on the highway

I can hear them rebels yell

And I know no one can sing the blues

Like Blind Willie McTell

With some fine young handsome man

He’s dressed up like a squire

Bootlegged whiskey in his hand

There’s a chain gang on the highway

I can hear them rebels yell

And I know no one can sing the blues

Like Blind Willie McTell

Well, God is in His heaven

And we all want what’s His

But power and greed and corruptible seed

Seem to be all that there is

I’m gazing out the window

Of the St. James Hotel

And I know no one can sing the blues

Like Blind Willie McTell

In a soliloquy from a hotel window, Dylan describes the world of exile and ghosts emanating from the Civil War. He sees these martyrs perfectly, but he is not destined to join them, only to witness. He finds imperfection everywhere, especially in himself, carrying a voice that can never match a true seer. And still, his only choice is to keep telling the tale, a singer in the image of Blind Willie McTell just as "we all want what's His."

And we all want what’s His

But power and greed and corruptible seed

Seem to be all that there is

I’m gazing out the window

Of the St. James Hotel

And I know no one can sing the blues

Like Blind Willie McTell

In a soliloquy from a hotel window, Dylan describes the world of exile and ghosts emanating from the Civil War. He sees these martyrs perfectly, but he is not destined to join them, only to witness. He finds imperfection everywhere, especially in himself, carrying a voice that can never match a true seer. And still, his only choice is to keep telling the tale, a singer in the image of Blind Willie McTell just as "we all want what's His."

Leonard Cohen also describes his work as an echo of another grand story, the biblical landscape. In 1993, Arthur Kurzweil asked him about a line from "The Future" saying "I'm the little Jew who wrote the Bible." Cohen explains:

Oh, I am the little Jew who wrote the Bible. "You don't know me from the wind/You never will, you never did." I'm saying this to the nations. I'm the little Jew who wrote the Bible. I'm that little one. "I've seen the nations rise and fall/I've heard their stories, heard them all/But love's the only engine of survival." I know what a people needs to survive. As I get older I feel less modest about taking these positions because I realize we are the ones who wrote the Bible and at our best we inhabit a biblical landscape, and this is where we should situate ourselves without apology. The biblical landscape is our urgent invitation and we have to be there. Otherwise, it's really not worth saving or manifesting, or redeeming, or anything. Now, what is the biblical landscape? It's the victory of experience. That's what the Bible celebrates. So the experience of these things is absolutely necessary.

Sometimes Cohen and Dylan find themselves parked at the exact same spot, interpreting the same sacred story. In one case, it is indeed part of the biblical landscape. Dylan places the Sacrifice of Isaac on Highway 61, which runs right down the center of the United States, beginning in Minnesota at the Canadian border near Dylan’s birthplace and ending in New Orleans at the Gulf of Mexico. Also known as the Blues Highway, Highway 61 was a primary route of exodus of slaves from the South towards the industrial cities of the North "where many martyrs fell." As Dylan hears it:

Oh God said to Abraham, 'Kill me a son'

Abe says, 'Man, you must be puttin' me on'

God say, 'No.' Abe say, 'What?''

God say, 'You can do what you want Abe, but

The next time you see me comin' you better run'

Well Abe says, 'Where do you want this killin' done?'

God says, ‘Out on Highway 61.’

Abraham is an easily corruptible huckster who builds an altar for his own son, a mythic model for four successive examples of the blind leading the lame. Cohen has a similar take on the blindness of the father in "The Story of Isaac." According to the biblical account, Isaac was blind. In Cohen's telling he sees everything, and the song squeezes paternal, authoritarian cruelty for all it is worth:

You who build these altars now

to sacrifice these children,

you must not do it anymore.

A scheme is not a vision

and you never have been tempted

by a demon or a god.

You who stand above them now,

your hatchets blunt and bloody,

you were not there before,

when I lay upon a mountain

and my father's hand was trembling

with the beauty of the word.

This formative myth seems all but impossible to shake--just like the Law.

to sacrifice these children,

you must not do it anymore.

A scheme is not a vision

and you never have been tempted

by a demon or a god.

You who stand above them now,

your hatchets blunt and bloody,

you were not there before,

when I lay upon a mountain

and my father's hand was trembling

with the beauty of the word.

This formative myth seems all but impossible to shake--just like the Law.

The Law

|

| Franz Kafka |

In Franz Kafka's “Before the Law” a man from the country wastes his entire life waiting to enter the gate containing the Law. On the verge of death he discovers that the door he has been waiting behind had been meant for him all along if only he had had the courage to open it.

Dylan's “Senor (Tales of Yankee Power)" offers a stunningly close parallel to Kafka's conflict. Yet his hero, standing alongside the messianic figure of Senor, wants to fight back:

Senor, senor, do you know where we're headin'?

Lincoln County Road or Armageddon?

Seems like I been down this way before.

Is there any truth in that, senor?

How long are we gonna be ridin'?

How long must I keep my eyes glued to the door?

Will there be any comfort there, senor?....

Senor, senor, let's disconnect these cables,

Overturn these tables.

This place don't make sense to me no more.

Can you tell me what we're waiting for, senor?

Dylan's freedom comes in kicking up against a force that looms too large for his comfort, a myth whose faces and names must be rearranged. When Cohen sees a seemingly immutable force, he bows to it and waits almost like Kafka's man from the country. But rather than falling to weakness and silence in his submission, Cohen makes the force of the will of the law his own. Consider "If It Be Your Will":

If it be your will

That I speak no more

And my voice be still

As it was before

I will speak no more

I shall abide until

I am spoken for

If it be your will

If it be your will

That a voice be true

From this broken hill

I will sing to you

From this broken hill

All your praises they shall ring

If it be your will

To let me sing

From this broken hill

All your praises they shall ring

If it be your will

To let me sing

That I speak no more

And my voice be still

As it was before

I will speak no more

I shall abide until

I am spoken for

If it be your will

If it be your will

That a voice be true

From this broken hill

I will sing to you

From this broken hill

All your praises they shall ring

If it be your will

To let me sing

From this broken hill

All your praises they shall ring

If it be your will

To let me sing

Dylan and Cohen are in continual dialogue and conflict with the Will of the Law, but their faith in their own creative powers to redirect myth defines a code for managing the friction it fuels--and making it hum. As Dylan sings in "Absolutely Sweet Marie," telling truth to the Law invites a person to stake a unique claim to it. But real outlaws "outside the law" can only survive if they craft a new code as part of this challenge:

Well, six white horses that you did promise

Were fin’lly delivered down to the penitentiary

But to live outside the law, you must be honest

I know you always say that you agree

But where are you tonight, sweet Marie?

Were fin’lly delivered down to the penitentiary

But to live outside the law, you must be honest

I know you always say that you agree

But where are you tonight, sweet Marie?

So too in Cohen's "Like a Bird on a Wire":

Oh like a bird on the wire,

like a drunk in a midnight choir

I have tried in my way to be free.

like a drunk in a midnight choir

I have tried in my way to be free.

True freedom is contradictory. A bird holds to a wire even if it could have chosen to fly away. The one "born with a golden voice" does not leave the chorus to sing solo. Freedom comes from abiding tensions between the obvious choices myths suggest and deeper truths that emerge only after challenging them and living with them.

As Joseph Campbell said when we started this conversation: "Myths are public dreams. Dreams are private myths." Great artists make hard-earned offerings of both.

As Joseph Campbell said when we started this conversation: "Myths are public dreams. Dreams are private myths." Great artists make hard-earned offerings of both.

1 comment:

Thanks for the series. You have an interesting perspective. I would think they points made could bear some longer exposition.

Post a Comment