Creation Myths

In the beginning—in our first session, that is—there were Bob Dylan and Leonard Cohen. But where do they come from and what are they for?

Both have crafted personal myths describing unusual origins and a unique calling echoing mythic heroes of old, and because they are both the tellers and the heroes of their own tales, each plays a double role—Homer and Odysseus at the very same time. This is just one of the many post-modern twists Dylan and Cohen bring to the ancient art of mythmaking.

From the start Dylan is a fiercely independent wanderer. He accepts a calling "to make shoes for everyone, even you/but still I walk barefoot" in "I and I" (which appears below). Even moments of grace like the midnight strolls in "I and I" or the "mystic garden" of "Ain't Talkin'" (which will appear a few sessions later), Dylan does his seeking alone.

Leonard Cohen is also a serial seeker, but particularly in the later portion of his career, he positions his purpose differently than Dylan. Cohen dwells in a kind of humility or simplicity of service that Dylan blends into more complex, challenging narratives. Hear how Cohen draws upon the image of a servant in "Show Me the Place," accepting that he is a vessel for a higher purpose. He calls out for resolution for ancient spiritual conundrums of suffering—"when the Word became a man" or how to move a mythic Sisyphean stone—and asks for a partner from other realms to understand the universe, sing-saying in a low-pitched, pleading purr: "I can't move this thing alone."

Leonard Cohen is also a serial seeker, but particularly in the later portion of his career, he positions his purpose differently than Dylan. Cohen dwells in a kind of humility or simplicity of service that Dylan blends into more complex, challenging narratives. Hear how Cohen draws upon the image of a servant in "Show Me the Place," accepting that he is a vessel for a higher purpose. He calls out for resolution for ancient spiritual conundrums of suffering—"when the Word became a man" or how to move a mythic Sisyphean stone—and asks for a partner from other realms to understand the universe, sing-saying in a low-pitched, pleading purr: "I can't move this thing alone."

Dylan makes no bones about knowing that he and everyone must serve a greater power:

Dylan makes no bones about knowing that he and everyone must serve a greater power:You may call me Terry, you may call me Timmy

You may call me Bobby, you may call me Zimmy

You may call me R.J., you may call me Ray

You may call me anything but no matter what you say

You may call me R.J., you may call me Ray

You may call me anything but no matter what you say

You’re gonna have to serve somebody, yes indeed

You’re gonna have to serve somebody

Well, it may be the devil or it may be the Lord

But you’re gonna have to serve somebody

His narrators often speak of being vessels of higher purpose, but they are "still on the road lookin' for another joint." Even the heavenly forces his narrators know well cannot pin Dylan's heroes down. Always on the move, Dylan does not want or need a partner to help him. Cohen longs for a partner, and when he finds one, he holds on to him or her tight.You’re gonna have to serve somebody

Well, it may be the devil or it may be the Lord

But you’re gonna have to serve somebody

Masters and Teachers

Relationships to teachers reflect this same difference in approach. For Dylan, even if his high school yearbook lists his life ambition as being to "follow Little Richard," the master teacher of the first portion of his career is Woody Guthrie.

"Last Thoughts on Woody Guthrie," written and performed in 1963, is classic ode of a young man to his teacher. It ends like this:

And where do you look for this hope that yer seekin'

Where do you look for this lamp that's a-burnin'

Where do you look for this oil well gushin'

Where do you look for this candle that's glowin'

Where do you look for this hope that you know is there

And out there somewhere

And your feet can only walk down two kinds of roads

Your eyes can only look through two kinds of windows

Your nose can only smell two kinds of hallways

You can touch and twist

And turn two kinds of doorknobs

You can either go to the church of your choice

Or you can go to Brooklyn State Hospital

You'll find God in the church of your choice

You'll find Woody Guthrie in Brooklyn State Hospital

Where do you look for this lamp that's a-burnin'

Where do you look for this oil well gushin'

Where do you look for this candle that's glowin'

Where do you look for this hope that you know is there

And out there somewhere

And your feet can only walk down two kinds of roads

Your eyes can only look through two kinds of windows

Your nose can only smell two kinds of hallways

You can touch and twist

And turn two kinds of doorknobs

You can either go to the church of your choice

Or you can go to Brooklyn State Hospital

You'll find God in the church of your choice

You'll find Woody Guthrie in Brooklyn State Hospital

And though it's only my opinion

I may be right or wrong

You'll find them both

In the Grand Canyon

At sundownI may be right or wrong

You'll find them both

In the Grand Canyon

After Guthrie—but for a very public commitment to being "Property of Jesus" in the 70's—Dylan never commits to another single teacher or path in the overall arc of his songs. He learns from everyone and no one, singing: "Don't follow leaders/Watch the parking meters." Recently, the Never Ending Bootleg Series revealed a tune—"Working on a Guru"—that pokes fun at the foolish move to become beholden to a single master:

Rain on the ground, windshield wipers movin',

Water all around, I sure don't feel like groovin'.

I'm working on a guru,

Yes, I'm working on a guru,

But I'm working on a guru, before the sun goes down.

Working on a guru,

Working on a guru,

Well, it's true, it could be you ...

I'm working on a guru

In some ways, Dylan's most poignant expression of being a following is his resigned acceptance of fate, that he is a cog in the great wheel of life, as in "Every Grain of Sand":

I hear the ancient footsteps

like the motion of the sea

Sometimes I turn, there’s someone there,

Sometimes I turn, there’s someone there,

other times it’s only me

I am hanging in the balance

of the reality of man

Like every sparrow falling,

Like every sparrow falling,

like every grain of sand

In the lyrical flow of a psalm, Dylan's ultimate teacher is a sense and spirit of creation itself.

Leonard Cohen seeks real people of every kind to be his teachers, a litany of poets, lovers, scholars, musicians, and spiritual masters that he cites at every stage of his career:

I knew the words of every song.

Did my singing please you?

No, the words you sang were wrong.

Who is it whom I address,

who takes down what I confess?

Are you the teachers of my heart?

We teach old hearts to rest.

Oh teachers are my lessons done?

I cannot do another one.

They laughed and laughed and said, Well child,

are your lessons done?

are your lessons done?

are your lessons done?

"Master Song" plays with this motif as part of a romantic tangle, indicating how thick master/disciple themes are in Cohen's mythic imagination.

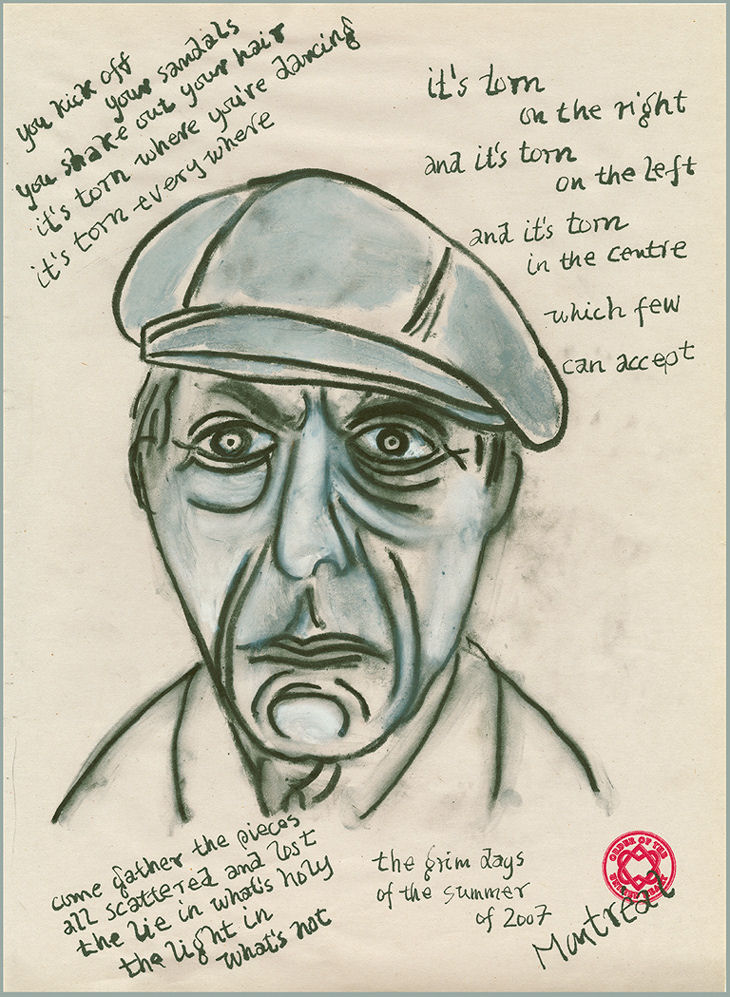

Book of Longing (2006), collection of poetry and drawings, is full of gestures of love and admiration for teachers, particularly for Roshi, Cohen's master of several decades, including a period living as monk at a Zen monastery on Mount Baldy outside of Los Angeles.

HIS MASTER’S VOICE

After listening to Mozart

(which I often did)

I would always

Carry a piano

Up and down

Mt. Baldy

And I don’t mean

A keyboard

I mean a full-sized

Grand piano

Made of cement

Now that I am dying

I don’t regret

A single step

ROSHI

I never really understood

what he said

but every now and then

I find myself

barking with the dog

or bending with the irises

or helping out

In other little ways

ROSHI AT 89

Roshi’s very tired

he’s been lying on his bed

He’s been living with the living

and dying with the dead

But now he wants another drink

(will wonders never cease?)

He’s making war on war

And he’s making war on peace

He’s sitting in the throne-room

on his Original Face

and he’s making war on Nothing

that has Something in its place

His stomach’s very happy

The prunes are working well

There’s no one going to Heaven

And there’s no one left in Hell

And as has he had done since his first brush with fame as an upstart Canadian poet in the 50's and 60's, Cohen calls out the fellow writers who helped shape his own voice:

LAYTON’S QUESTION

Always after I tell him

what I intend to do next,

Layton solemnly inquires:

Leonard, are you sure

you’re doing the wrong thing?

LORCA LIVES

LORCA LIVESLorca lives in New York City

He never went back to Spain

He went to Cuba for a while

But he’s back in town again

He’s tired of the gypsies

And he’s tired of the sea

He hates to play his old guitar

It only has one key

He heard that he was shot and killed

He never was, you know

He lives in New York City

He doesn’t like it though

Cohen and Dylan both express awe, humility, longing, and praise as they try to make their way towards wisdom on a twisting mythic path. Dylan, launched into public consciousness as a hipster reimagining of Woody Guthrie, avoids aligning the heroes of his music with any one figure or school of thought. It's also worth noting that even though most of his songs as written in the first person, Dylan often denies in interviews that his work is auto-biographical. Maybe it is and maybe it is not. The point is that Dylan's work is a sophisticated mix of mythic commentary and confession. Cohen unabashedly grounds himself in people and disciplines that define his path and shares his journey lucidly and unadorned.

Next Up: Dreams and Visions

In the joint mode of mythic seekers and bards of themselves, Dylan and Cohen describe unique origins and purpose and wrestle with who and what serve as their guides for their purposes. Tomorrow we will see how each fleshes out their calling with dreams and visions of life, the universe, and everything.

Read about Dreams and Visions here.

No comments:

Post a Comment